Pine trees in the mist - Hasegawa Tohaku

We can’t take our theories with us. Wherever we go, the bag of ideas we lug around only slows us down. Especially if that journey is inward, downward, toward the underlying, interpenetrating no-field. Upward in the clear skies we can rest our concepts in a kind of vibratory coherence with something larger than us—our bag of tricks resonate. But the move toward freedom is beyond all that. Beyond the unity and even the looking glass itself, which we have carried forth throughout our lives. Beyond even the ground of awareness - neither the stream of being nor its witness can continue forever. We are all vagrants without possessions fumbling about in the promised land.

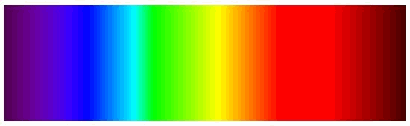

The rainbow of life

is self-spontaneous

the balanced mind

need not reach for it

Another teaser from that book with no deadline:

We are responsible for how we frame the workings of the mind: Both despair and beauty are readily available interpretations.

For example, we can approach the idea “all is inference”—a basic tenant of contemporary mind and brain sciences—and get all dark and gloomy about it: “Oh nothing matters! It’s all just made up!”. Or, we can recognise the immense exquisiteness and creative potential that these facts necessitate.

We may be able to see that our mind and its inferences are not a disconnected thing that happens inside of our skulls, but as something that binds us to everything else. It isn’t something we’re doing but something we’re participating in. In a way, we’re all playing a role in God’s guesswork, in God’s creativity.

We have a deep solitude in our humble perspective—the inferences of our particular mind—and yet that perspective is partly determined by all the other perspectives out there. Our perceptions are part of something grand, marvellous beyond our imagination, continuous and co-dependent upon the stars and the oceans and all the creatures within them.

We are like a web of crystalline prisms each reflecting each other in distinctive ways—each gently nudging the other towards new innovations of perception. A blossoming birthed out of the groundless ground that is the one thing we all truly share. The order and coherence you experience in the present is your divine capacity for scientific art—data-driven creativity! You are an organism participating in the spawning of something from nothing. How dare you not love yourself.

From inference to emptiness

My first encounter with emptiness occurred (surprisingly) in the context of purely scientific inquiry. At the time, I wouldn’t have called it emptiness, but so it was. I was preparing my PhD proposal and was reflecting on issues of categorisation, you know, as you do. I wondered: What actually makes a ‘thing’ a ‘thing’? How are we able to perceive ‘objects’ like chairs, tables, and trees, in a field of messy light, vibration, and molecules, made all the more confusing by mismatches in time and space?

In my search for a solution, I came across various paradoxes revealing that there is, in fact, no real separation between things at all! It was a shocking discovery. A moment that rocked me a few feet off the ground. And I remember it well.

I was living in a small apartment along the river a few streets from the university where I used to skate a longboard back and forth between campus and home. On this day, I think a Sunday, I woke up with a light hangover at around 6am. While still in bed, I decided to sit up (only just enough to write comfortably) and continue reflecting on this terrible matter of ‘things’.

An insight dawned.

It was the kind of insight that the philosopher Rob Sips called an “anti-aha” moment that deconstructs what one knows, rather than builds upon it. The insight came because I reflected one by one on every category and object I could possibly think of. In the theatre of my mind, I tested them all for exceptions to the rule. Shockingly, there were always exceptions! There was always an ambiguous case. No categories—none at all—had any real, consistent foundation. They were completely made up.

Mainstream cognitive science also argues that apparent physical objects such as a table or a chair is dependent upon a constellation of features, or statistical regularities, and there are ambiguous cases for every category. You can have chairs that look like tables and tables that you sit on. You can put your plate on a chair and eat from it, if you want to.

Subatomically, the leaf of a tree is continuous with the sky and the roots with the Earth. In philosophy, this is known as the problem of vagueness; wherein any object that we try to classify as a truly existing ‘natural kind’ breaks down upon careful investigation. Strict definitions cannot be found even for biological species.

It is illustrated by the Sorites Paradox, also known as the bald man problem or the paradox of the heap: How many hairs makes a man bald? How many grains of sand make a heap? It is, in every case, arbitrary. Reality is far too wavy, not particular enough, and perhaps best analogised by the color spectrum:

You see where this is going.

Categories, “things”, are man-made, mind-inferred, and therefore, empty of real, inherent, existence. All is inference is really a contemporary neuroscientific teaching about emptiness. Suckers.

Obviously we need the categories. They serve a valuable purpose and they are connected to the phenomena of the world and other people, but the categories themselves are without any consistent foundation.

When you notice this experientially it hits you pretty hard. Of course, in order to function in the world we need to act as if those things do really exist. Without the categories we wouldn’t be able to make sense of what to eat and what not to eat. But it is one thing to eat a sandwich and quite another to believe in the inherent existence of such a thing called a sandwich. The latter is not necessary, and it is very sticky indeed.

Emptiness is a powerful, psychoactive idea with direct consequences to our experience if we integrate it. It’s also the result of careful observation of one’s own experience. It’s a way of looking at things, it’s the nature of things, and it’s the states that follow.

For example, if we look closely at an emotion, we see that it is made of continuous blobs of sensations within the body, often bound together with bundles of thoughts, as well as the bodies arousal system. When you look closely, there’s no emotion to be found, only different components that are themselves up for interpretation.

Put in another way: Every seeming separate thing that we perceive arises in dependence on other things. Upness has no consistent reality in itself except in contrast to the notion of downness and both of these are dependent on many other reference points, including the very necessity of a reference point.

It is only when we abstract away from life—when we step into time and continuity—that we find squares, numbers, and things. Underlying abstraction is flux, paradox, and patterns. Categories and objects exist only in the mind and must be learned. They are like tiny stories, concrete only once we’ve constructed them. And yet, they can be a profound source of meaning so long as we don’t make gurus out of them.

All is inference makes a similar point about emptiness in a different way. It reveals that what we are encountering as our experience and world is in fact an idea—an idea that can take innumerable forms and change at any moment. Just try taking magic mushrooms and looking at the carpet. Or think about your lover during a fight or while making love. What was once one thing becomes something quite different. Even visual illusions are teachings on emptiness—perhaps that’s why we find them so fascinating.

It’s valuable to have direct experiential encounters with this emptiness and to reflect on it. It may begin as a conceptual notion, but it is really when we look at our experiences and ideas deeply and recognise this no-substance at the heart of them that the mind can begin to let go.

Realising the emptiness of inferences is really a tool for letting go. And we must ultimately see this emptiness intimately as the no-essence of every single thing in order to transform our minds into something more resilient and beautiful: Something less sticky.

Somehow we must be brave enough to turn the lens of emptiness upon the lens itself.

If we can see our mirages for what they are—as empty inferences—then the mind naturally inclines towards releasing them. Why would I hold onto an image that has no essential nature? Why would I grasp at a guess? Why would I get stuck on a perspective or ideology if I truly understand that it’s just an inference? Why would “I”—an inference—try to control the appearances?

As it is stated in the Lankavatara Sutra:

“Because the various projections of people’s minds appear before them as objects, they become attached to the existence of their projections.” The solution, the Buddha of the text proposes, is simply “…becoming aware that projections are nothing but mind.”

All is inference applies to Buddhism, gurus, and science itself. Impressions of beauty that may hinder our ability to see the very beauty under our noses. They may ultimately become the source of our suffering as we place our bag of concepts on a pedestal above this moment, or worse, our families and our communities.

Stuckness is released by uprooting the habit of thingification: The tendency to give objects of mind objectivity—especially the self. It is about relaxing the tendency to project concreteness where it does not belong, where it causes us unnecessary hardship because we take it too literally.

We simply cannot dance so long as we imagine ourselves and others as stones.

We can’t even play because play presumes a free flowing imagination, which presumes a flexible reality. When we’re stuck in the mind we also get stuck in our bodies—we get stiff and awkward. We get the icky stench of stuckness.

If we can release the stickiness of thingification then phenomena begin to sort themselves out, finding their place in the garden of our mind. But this is not a post-modernism. It is an empirical hypothesis.

All concepts can be both pragmatic tools and also potentially obstacles, depending on circumstances. I don’t suggest that one walks around reciting a mantra that “oh, that person is just an empty inference and does not exist”. That is just avoidance. No, the wisdom of emptiness, which is the natural conclusion of the mind-sciences, is, like all teachings, a raft that is helpful during practice but not something we should bind ourselves to. It should not get us stuck in a particular frame.

Emptiness is precisely where we find form—afresh.

If we grasp at the notion of emptiness it can eat itself up when we recognise that emptiness is itself empty. All is inference is itself an inference. That which is speaking of these concepts and writing them here is an empty inference. That which is reading these words is an empty inference.

This whole chapter is an empty inference and these words are without any consistent nature. The idea of an empty inference is an empty inference. That which we call an empty inference is what? Is it dark and gloomy, or it is spontaneous and beautiful? It is up for interpretation.

But one thing is hard to argue: it is free.

it is marvellous

the existence of things

especially those that live

perhaps we marvelled ourselves into existence

enthralled by our own genius

we dove into a painting

The above is a beautiful piece of writing, Thank you.

There is much to appreciate in Sunyata, your particular take is refreshing.

This article is a piece of wisdom full of emptiness! Thanks for such a beautiful explanation, Ruben.